In my many years of work with Fondazione Arte della Seta Lisio I have had occasion to meet a host of truly dedicated colleagues, scholars and students: a broad-based community of people who all share a love for weaving and for textiles in general.

Thanks to two of these acquaintances, and to the support of the foundation, in early 2016 I flew to New Delhi for ten days, days that were filled with discoveries and intense study. Many of the details were organised prior to my departure by my kind and thoughtful fellow adventurers: Abbas Khan, a student at past ‘Analysis’ and ‘Figured Fabric Design’ courses and an aficionado of the precious fabrics of his native land, India; and Barbara S. Pickett, a colleague and friend I have known for at least two decades, a scholar of velvet techniques and the life of a study programme for U.S. students who travel to Florence to learn the jacquard weaving methods.

About three hours after I landed, I rented a car to travel to meet Ashdeen Lilaowala at his workshop south of New Delhi. A dive into the chaos of Indian traffic took me to a spacious room where ten or so young artisans were absorbed in ‘drawing’, with silk thread, on lengths of fabric stretched tightly on frames set a few dozen centimetres above the floor.

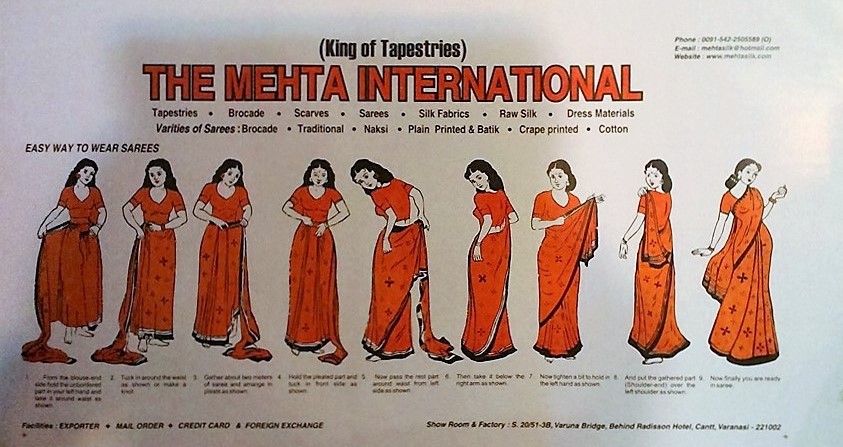

In the adjoining room, a showcase of completed works: saris marvellously decorated with embroideries in contrasting colours in designs with a contemporary graphics flair. And thus, I learned of the ‘rebirth’ of the sari in India and of the fashion among India’s urbanised, cosmopolitan young women of including these ultra-traditional garments in their wardrobes.

The next day was devoted to a lengthy visit to the Crafts Museum: the textile section is full of surprises and includes a perfectly assembled and warped, fully-operational drawloom! The museum is sited in a large garden, isolated from the incessant noise of traffic: another non-negligible reason for visiting.

The following day, I went to see the hushed, elegant Kashmir Looms showroom, where I viewed many works in precious hand-spun and hand-woven pashmina, of a quality decidedly higher than any of the many products sold everywhere under this name.

My first days in Delhi were over. A short flight, just over two hours, would have taken me to Varanasi, to the places I was most looking forward to visiting and where I was to meet Barbara and the small group of textile artists who had flown in from the States. A dense fog delayed my flight for quite a few hours; thus, instead of reconnoitring the famous sacred city of Buddhism and Hinduism, I remained ‘parked’ for most of the day in the capital’s modern, impersonal airport. Fortunately, I was able to finally join the group, just in time for dinner. The Hotel Ganges View, where we stayed, was once a private home and is truly charming.

We didn’t have much time: we devoted our first day to a guided tour of the city, from 6:00 a.m. well into the evening.

We observed rituals along the Ganges, explored the narrow streets of the centre, visited the archaeological museum, the Durga Mandir and a huge temple, crowded with the faithful, took a short ride in a rickshaw and visited a textile workshop. Our time at the workshop extended far beyond that foreseen by our guide and completely upset his plans. We skipped lunch, with no regrets whatsoever, as we learned about the uses and types of local textiles.

All of this information proved very useful the very next day, the day we had all been waiting for: our visit to the workshop supported by well-known scholar Rahul Jain , where, at his request and under his supervision, polychrome velvet is woven on a drawloom. None of us had ever seen a drawloom, except in photographs or in Lyon, where such a loom is assembled and probably operational – but the one here was really used for weaving!

Not that the work is easy, or even rapid. Four workers were busy at the loom – essentially, the entire family. The elderly father saw after the creel, mounted in a manner very different from ours but threaded for three colours with hundreds of hanging bobbins.

The head of the family wove and his brother’s task was to select the heddle loops; his wife, instead, saw to cleaning the shed and to the movements of the selvedges .

We observed, asked for explanations and took photos, and we spoke numerous times on the phone with Rahul Jain, who despite being in Delhi spoke speak Hindi with the weavers and English with us. With a little help from our driver and gesturing our way along, we managed to understand one another – or at least so I hope. In India, the weavers work on the so-called pitlooms, looms with the treadles set below floor level and the warp beams a few centimetres from the floor.

This is an eminently practical solution that lends great stability to the loom and relieves the weavers’ fatigue, but it makes watching an arduous task: the space around the loom is reduced to a minimum and the treadles are difficult to see.

Near the end of our visit, the weavers brought in some of their fabrics, intended for wear as stoles: lancé taffetas with metallic weft threads and small brocade motifs.

I bought one in shades of pink and gold – an inspired purchase!

It was Sunday, and we had missed our chance to visit the market to buy the beautiful buffalo-horn shuttles, but we decided to go the next day. So we returned to our hotel to rest and think over all we had seen and learned. On the bus on the way back that’s all we talked about – and even before and during dinner, all our attention was still focused on velvets, saris and looms.

Before dinner I had occasion to visit a small Khadi shop I had seen along the road. The shop sold fabrics woven by hand at the associated cooperatives: local silks (‘non-violent’; that is, from cocoons from which the larvae have already emerged as moths) and kashmir and ultrafine cottons. There were also hand-woven cotton handkerchiefs. I bought a few, for 100 rupees each, an unbelievable price. When I returned from this short discovery trip I showed off my ‘treasures’ – and the rest of the group decided to visit the shop as well.

The next day was the last of my stay on the banks of the Ganges. Early in the morning, we went to the Bari Bazaar – the central market, one might say – accompanied by Sribhas Supakar, a designer who is very active in the city and who knows practically everyone.

We visited a workshop that weaves lampases for the Tibetan Buddhist monks and another, specialised in pashminas, passing through streets and alleyways where silk was being degummed, dyed and warped.

Once back in Delhi and having discovered the ultra-modern, truly efficient underground, I finally met up with Abbas, who had just returned to India. We stopped for tea at the lounge of the luxury Hotel Le Méridien and another India opened up before my eyes, the protected India of the well-to-do.

We made a quick visit to the Cottage Industries Emporium where a medley of beautiful, interesting items were on sale, but we were too tired to take advantage of the offer.

We met the next morning and paid a visit to Sanjay Garg at his studio/showroom, where I learned more about the sari revival and the beautiful products of the company founded by the designer just seven years ago: Raw Mango.

Adrift in a sea of gorgeous, brightly-coloured cottons and silks, and surrounded by sales assistants and clients, I asked him a thousand questions; nor did I miss the opportunity to interview a lovely girl with a very British accent who was selecting a beautiful stole there in the showroom.

The clients, I gathered, are all or almost all Indians, residents of India or members of the country’s far-flung expatriate community, who choose to dress in garments inspired by tradition and who know how to wear them to best effect.

After what I might call an ‘interesting’ lunch of Chinese food interpreted according to Indian taste – very spicy!! – we paid a visit to renowned textile scholar Rahul Jain, who received us at his home amidst some of the fabrics from the Mughal and Safavidi traditions which have been reconstructed thanks to his studies and the ‘digs’ conducted with the Varanasi weavers, the same people I had visited some days earlier.

I found many answers to many questions but my thirst for knowledge only increased: I must find my way back to India!

Everyone knows that India is a paradise for anyone interested in textiles – but actually being there . . . well, that’s something else entirely!